welcome

|

||||||||||||

______WAR______ These 127 essays, although organized under seven headings, have one underlying theme: opposition

to the warfare state that robs us of our liberty, our money, and in some cases our life. Conservatives who decry

the welfare state while supporting the warfare state are terribly inconsistent. The two are inseparable.

Libertarians who are opposed to war on principle, but support the state’s bogus “war on terrorism,” even as they

remain silent about the U.S. global empire, are likewise contradictory. In chapter 1, “War and Peace,” the evils of war and warmongers and the benefits of peace are examined. In chapter 2, “The Military,” the evils of standing armies and militarism are discussed, including a critical look at the U.S. military. In chapter 3, “The War in Iraq,” the wickedness of the Iraq War is exposed. In chapter 4, “World War II,” the “good war” is shown to be not so good after all. In chapter 5, “Other Wars,” the evils of war and the warfare state are chronicled in specific wars: the Crimean War (1854–1856), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), World War I (1914–1918), the Persian Gulf War (1990–1991), and the war in Afghanistan (2001–). In chapter 6, “The U.S. Global Empire,” the beginnings, growth, extent, nature, and consequences of the U.S. empire of bases and troops are revealed and critiqued. In chapter 7, “U.S. Foreign Policy,” the belligerence, recklessness, and follies of U.S. foreign policy are laid bare. Chapter One - War and Peace ______[p1]

Listen to "Christianity and WAR" on Spreaker.

WAR

The War To End All Wars

March 26, 2004

One hundred and fifty years ago, France and Great Britain intervened in what was, and should have remained, a dispute between Russia and Turkey. The official beginning of what came to be called the Crimean War was on March 28, 1854, when Great Britain and France declared war on Russia. Coming between Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 and the beginning of World War I in 1914, the Crimean War should have been the “war to end all wars” instead of being a precursor to the carnage of the war that made “the world safe for democracy.” There are three things that came out of the Crimean War that most people are familiar with but have no idea that they are connected with it: the nurse Florence Nightingale, the poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” and the novel War and Peace. Florence Nightingale (1820—1910) was the famed pioneer of nursing and reformer of hospital sanitation methods. After hearing of the deplorable conditions that existed in the British Military Hospital at Scutari, opposite of Constantinople, she arrived in the Crimea with 38 nurses on November 4, 1854, and soon began to improve the conditions at the hospital. “The Charge of the Light Brigade” was the poem written by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809—1892) that immortalized the disastrous British cavalry charge which occurred during the Crimean War at the Battle of Balaclava on October 25, 1854. “Forward, the Light Brigade!” Was there a man dismay’d? Not tho’ the soldiers knew Some one had blunder’d: Their’s not to make reply Their’s not to reason why, Their’s but to do and die: Into the valley of Death Rode the Six Hundred. Set in Russia during the Napoleonic Era, War and Peace, by the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828—1910), is the epic novel published between 1865 and 1869. Although most people have never read it, because it contains 365 chapters, War and Peace is the book usually mentioned when one wants to compare some daunting task to reading an unusually large book. The connection between War and Peace and the Crimean War? Tolstoy was a Russian second lieutenant in the Crimean War, and therefore an eyewitness to battle scenes he so realistically describes in this novel. Located in southern Ukraine, the Crimean peninsula juts into the Black Sea and connects to the mainland by the Isthmus of Perekop. Its area is about 9700 square miles. Dry steppes, scattered with numerous burial-mounds of the ancient Scythians, cover more than two-thirds of the peninsula, with the Crimean mountains in the south rising to heights of 5,000 ft. before dropping sharply to the Black Sea. Various peoples have occupied the Crimean peninsula over the years: Goths, Huns, Scythians, Khazars, Greeks, Kipchaks, Mongols. The Ottoman Turks conquered the region in 1475. In 1783, the whole of the Crimea was annexed to the Russian Empire. The Crimea was the scene of some bloody battles in the Second World War. It was also the site of the “Big Three” (Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin) Conference held in the former palace of Czar Nicholas at Yalta, a city on the Crimean southeastern shore of the Black Sea. It was here during the week of February 4—11, 1945, that Roosevelt delivered Eastern Europe to Stalin. The underlying cause of the Crimean War was the Eastern Question — the international problem of European territory controlled by the decaying Ottoman Empire. The immediate causes of the Crimean War were religious. Now, there is nothing the least bit “religious” about war, but, without a complete separation of church and state, religion is often used by the state as a pretext for war. Russia (Orthodox) was engaged in a dispute with France (Catholic) over the guardianship of the “Holy Places” in Palestine, and a dispute with the Ottoman Turks over the protection of the Orthodox Christians subject to the Ottoman sultan. Russia demanded from the Turks that there be established a Russian protectorate over all Orthodox subjects in the Ottoman Empire. After Turkey refused, Russia, in July of 1853, occupied the Ottoman vassal states of Moldavia and Walachia. The czar made the claim that “by the occupation of the Principalities we desire such security as will ensure the restoration of our dues. It is not conquest that we seek but satisfaction for a just right so clearly infringed.” In October of the same year, the Ottoman Turks declared war on Russia. War between Russia and Turkey was nothing new, as the Russo-Turkish Wars (1768—74, 1787—92, 1828—29) evidence. They had first clashed over Astrakhan in 1569. Although Constantinople had fallen to the Turks in 1453, the Ottoman Empire was in decline, and Russia, since the time of Peter the Great (1672—1725), had wanted to secure a warm-water outlet to the Mediterranean — at the expense of Ottoman territory. This naturally upset France and Great Britain, which saw Russian ambitions as a threat to the balance of power in the Mediterranean. Russia was given an ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of its forces from the principalities. When Russia refused, France and Great Britain, having already dispatched fleets to the Black Sea, declared war on Russia on March 28, 1854. The Anglo-Franco alliance was a precarious one. France and Great Britain had historically been enemies, but, like Herod and Pilate, who “were made friends together” when they allied to condemn Christ (Luke 23:1—12), they united to check the ambitions of Russia, under the guise of defending Turkey. Most of the subsequent fighting took place in the Crimea because of the strategic Russian naval base at Sevastopol on the southwestern coast. The accession of a new czar in Russia (Alexander II) and the capture of Sevastopol led to the Treaty of Paris (March 30, 1856) that ended the war and the dominant role of Russia in Southeast Europe. Britain and France saved the Ottoman empire, an empire that they would help destroy in World War I. The Crimean War is known for a number of “firsts”: deadly accurate rifles, significant use of the telegraph, tactical use of railways, life-saving medical innovations, trench combat, undersea mines, “live” reporting to newspapers, and cigarettes. But there is one other thing that began with the Crimean War that should have made it the war to end all wars: photography. Although photography had only recently been invented before the Crimean War, it had progressed enough so as to make it possible to photograph the horrors of war. The wet collodion process by Frederick Scott Archer (1813—1857), introduced in 1850, cut exposure times from minutes to seconds. War correspondents Thomas Chenery and William Russell relayed some of the horrors of war back to The Times in Britain. Thomas Agnew, of the publishing house Thomas Agnew & Sons, then proposed sending a photographer to the Crimea as a strictly private, commercial venture. The British government had previously made several official attempts to document the war with photographs. One effort ended in shipwreck, and none of the photographs survive from the other two. Enter Roger Fenton (1819—1869). Fenton, who had previously photographed the royal family, spent four months in the Crimea (March 8 to June 26, 1855) photographing the war. He had the cooperation of Prince Albert and the ministry of war, as well as the field commanders in the Crimea. After converting a horse-drawn wine merchant’s “van” into a mobile darkroom, Fenton, his assistants, horses, photographic van, and equipment were transported to the Crimea courtesy of the British government. He returned to Britain with 360 photographs and cholera. On September 20th, 1855, an exhibit of 312 of the photographs opened in London. Sets of photographs went on sale in November. Although the pictures were widely reviewed and advertised, when the war ended, interest in photographs of the war ended with it, and the entire stock of unsold prints and negatives were auctioned off by December of 1856. Fenton abandoned photography in 1862, putting an advertisement in the Photographic Journal to dispose of his equipment. In 1944, the Library of Congress purchased 263 of Fenton’s prints from one of his relatives. The Roger Fenton Crimean War photographs, thought to be Fenton’s proof prints made upon his return, can be viewed online and freely downloaded, including his most well-known photograph, “Valley of the Shadow of Death.” While Fenton’s photographs show plenty of scenes of military supplies, camp life, groups of soldiers, the leading figures of the allied armies, and landscape scenes, there are no scenes of combat or devastation. He wrote about scenes of death and destruction that he witnessed, but he did not photograph any of them. At the scene of the Light Brigade’s ill-fated charge, he saw “skeletons half-buried, one was lying as if he had raised himself upon his elbow, the bare skull sticking up with still enough flesh in the muscles to prevent it falling from the shoulders.” But whether it was because of an explicit directive from, or an implicit understanding with, the British government, the fact remains that Fenton witnessed the horrors of war, and had ample opportunity to photograph them, but didn’t. For political or commercial reasons, or both, the war was portrayed in the best possible light. A positive report was needed to counter negative press reports and to encourage the British nation to support the war effort. For this reason, Fenton’s photographs can be considered the first instance of photographic propaganda. The Crimean War destroyed the lives of over 200,000 men. How many Russians could have become another Boris Pasternak or Igor Sikorsky? How many British could have become another Christopher Wren or Isaac Newton? How many French could have become another Victor Hugo or Frdric Bastiat? How many Turks could have become another Mustafa Kemal or Ali Erdemir. God only knows. The Crimean War could have and should have been the war to end all wars. Instead, as A. N. Wilson remarks in The Victorians, it was the greatest blunder of the nineteenth century, setting up animosities and alliances that led to World War I and the continuing turmoil of Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia. For the latest book on the Crimean War, see Trevor Royle’s Crimea: The Great Crimean War 1854-1856.

The Horrors of War

July 9, 2004

“It is well that war is so terrible, lest we grow too fond of it.” ~ Robert E. Lee “The evils of war are great in their endurance, and have a long reckoning for ages to come.” ~ Thomas Jefferson Current Conflicts At the dawning of the year 2004, there were fifteen major wars in progress, plus twenty more “lesser” conflicts. According to Global Security, there are now conflicts raging in the following places:

Although the United Nations was founded “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind,” there have been more conflicts in the world since the founding of the UN than during any previous period in history. The United States maintains a global empire of troops and bases that would make a Roman emperor look like the mayor of a small town. War Too much has been written throughout history that glorifies war and the warrior who is sent by the state to do its bidding. Dying for one’s country — regardless of the circumstances that brought on the conflict — is seen as the ultimate sacrifice. To protest the war is to be a traitor. Being a professional soldier is viewed as one of the noblest of occupations. The death of enemy combatants is celebrated. Civilian casualties are written off as “collateral damage.” In the current Iraq war, before the phoney transfer of power on June 28, 855 American troops had died. That is 800 young men (and women) who will never gave their parents any grandchildren or who left behind grieving wives and children. Forgotten are the over 5000 military personnel who were injured, many of whom will endure suffering the rest of their life. And that number is just the “official” figure. The thousands of Iraqi troops killed or injured are not much of a concern to anyone — and neither are the Iraqi civilian casualties. General descriptions of the horrors of war can be read in any military history by John Keegan or Martin Gilbert. But more and more specific accounts of the horrors of war are beginning to see the light of day. Blood Red Snow: The Memoirs of a German Soldier on the Eastern Front and His Time in Hell: A Texas Marine in France are two recent books that explore the horrors of war from the individual soldier’s point of view. Chris Hedges’ What Every Person Should Know About War is a stinging indictment of the twin evils of the glorification of war and the concealment of its brutality. The recently published Intimate Voices from the First World War does all of those things and much more. What makes this book so unique is that the authors — twenty eight men, women, and children from thirteen different nations — because they were not writing for publication, had no particular statement to make other than to describe the effects of war on themselves and their surroundings. This is the ultimate in primary source material. From their research into hundreds of first-hand accounts, the editors of the book, Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, selected twenty-eight diaries or collections of letters written by soldiers and civilians who lived (and in some cases died) during World War I. Many of the diaries were found decades after the end of the war, and some in the last few years. A few are published here for the first time. The horrors of war are described here as no historian writing in the twenty-first century could describe them. But in addition to the accounts of death, destruction, and starvation, Intimate Voices also gives us an insight into the role of the state in warfare, the religious ideas of the combatants, the war’s demoralizing effect on women, and the regrets of soldier and civilian. The War The conflict we read about in Intimate Voices is the “great war” to “make the world safe for democracy” — the “war to end all wars.” The war began when Austria declared war on Serbia after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, during a state visit to Sarajevo, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian province of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The archduke had recently given an after-dinner toast in which he advocated peace: “To peace! What would we get out of war with Serbia? We’d lose the lives of young men and we’d spend money better used elsewhere. And what would we gain, for heaven’s sake? A few plum trees, some pastures full of goat droppings, and a bunch of rebellious killers.” His advice went unheeded, and resulted in the slaughter of over a million soldiers who fought for his empire, plus an untold number of ordinary citizens. Overall, 65 million men donned a miliary uniform, over 9.3 million soldiers died, 21 million soldiers were wounded, 7.8 million soldiers were captured or missing, and 6.7 million civilians died. The Cast of Characters The writers of the diaries and letters in Intimate Voices are a diverse lot. German soldier Paul Hub is a young recruit sent to make up for the heavy losses suffered by his advancing army. He married his sweetheart, whom he wrote to throughout the war, while home on leave in June of 1918. After a few days with his wife he returned to the front — only to die two months later. Polish widow Helena Jablonska survived the war and died in 1936. Austrian doctor Josef Tomann tends to the sick and wounded soldiers in a hospital in Przemysl. He contracted disease and died in May 1915, leaving behind a wife and a baby daughter. German officer Ernst Nopper, an interior decorator from Ludwigsburg, was killed in action on the Western Front, leaving a wife and two children. Serbian officer Milorad Markovic is the future grandfather of Mirjana Markovic, wife of Slobodan Milosevic. He survived the war, only to be captured by the Nazis in the next one. He made it through that one as well and died in 1967. Russian soldier Vasily Mishnin was reunited with his wife and two sons after the war. He went back to work at a furniture shop and died in 1955. Australian corporal George Mitchell finished the war as a captain. He wrote several books about World War I and served again in World War II. He died in 1961. Turkish second lieutenant Mehmed Fasih was captured by the Allies and released at the end of the war. He married in 1924 and lived until 1964. German doctor Ludwig Deppe returned to Dresden after the war. His subsequent fate is unknown. French captain Paul Truffrau returned to Paris after the war, where he became a teacher. He went on to fight and keep another diary in World War II. He died in 1973. Russian officer Dmitry Oskin joined the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. He advanced in the Communist Party but died suddenly in 1934, possibly a victim of a Stalinist purge. American officer John Clark survived the war and married his sweetheart, a Red Cross nurse. An unnamed Austrian officer wrote a diary that was found on his dead body in July of 1915. He died in mid-sentence. Russian soldier Alexei Zyikov was captured by the Germans. His diary was found by a Russian solider in Germany during World War II. German schoolgirl Piete Kuhr lived through the war and became a professional performer and then a writer. She and her family fled to Switzerland during World War II. She died in 1989. French schoolboy Yves Congar lived to become a priest, serve in World War II, and be made a cardinal. He lived until 1995. Klara Hess was the mother of the future Nazi Rudolf Hess. African Kande Kamara was from French Guinea. He fought for the French and returned home to West Africa at the end of the war. Forced to flee his village, he never saw his family again. British private Robert Cude returned to London after the war. He later appeared as an extra in a James Bond film. British officer Richard Meinertzhagen became a colonel and attended the Paris Peace Conference. He became an advocate of Zionism and later wrote Middle East Diary, about his experiences in the Middle East after World War I. He died in 1967. Canadian Winnie McClare was killed in May of 1917, within a month of his arrival at the front line. He was nineteen. The Horrors of War There is no better description of the horrors of war than an eyewitness description. German soldier Paul Hub writes to his girlfriend: I’ve already seen quite a lot of misery of war. . . . Maria, this sort of a war is so unspeakably miserable. If only you saw a line of stretcher-bearers with their burdens, you’d know what I mean. I haven’t had a chance to shoot yet. We’re having to deal with an unseen enemy. . . . Every day brings new horrors. . . . Every day the fighting gets fiercer and there is still no end in sight. Our blood is flowing in torrents. . . . That’s how it is. All around me, the most gruesome devastation. Dead and wounded soldiers, dead and dying animals, horse cadavers, burnt-out houses, dug-up fields, cars, clothes, weaponry — all this is scattered around me, a real mess. I didn’t think war would be like this. We can’t sleep for all the noise. Polish widow Helena Jablonska writes in her diary: Vast numbers of wounded are being brought in. Many of them die form severe blood loss, but the death toll would not be half as great were it not for cholera. It is spreading so fast that the cases outnumber those wounded and killed in battle. Everything has been infected: carts, stretchers, rooms, wardens, streets, manure, mud, everything. Soldiers fall in battle, where it is impossible to remove the bodies and disinfect them. They don’t even bother. Austrian doctor Josef Tomann writes in his diary: Starvation is kicking in. Sunken, pale figures wander like corpses through the streets, their ragged clothes hanging from skeletal bodies, their stony faces a picture of utter despair. . . . A terrifying number of people are suffering from malnutrition; the starving arrive in their dozens, frozen soldiers are brought in from the outposts, all of them like walking corpses. They lie silently on their cold hospital beds, make no complaints and drink muddy water they call tea. The next day they are carried away to the morgue. The sight of these pitiful figures, whose wives and children are probably also starving at home, wrings your heart. This is war. German officer Ernst Nopper writes in his diary: There are dead bodies everywhere you look. The villages have been completely destroyed. The fields are covered in so many graves it looks like moles have been at work. There are shell holes everywhere. Serbian officer Milorad Markovic writes in his diary: I remember things scattered all around; horses and men stumbling and falling into the abyss; Albanian attacks; hosts of women and children. A doctor would not dress an officer’s wound; soldiers would not bother to pull out a wounded comrade or officer. Belongings abandoned; starvation; wading across rivers clutching onto horses’ tails; old men, women and children climbing up the rocks; dying people on the road; a smashed human skull by the road; a corpse all skin and bones, robbed, stripped naked, mangled; soldiers, police officers, civilians, women, captives. Vlasta’s cousin, naked under his overcoat with a collar and cuffs, shattered, gone made. Soldiers like ghosts, skinny, pale, worn out, sunken eyes, their hair and beards long, their clothes in rages, almost naked, barefoot. Ghosts of people begging for bread, walking with sticks, their feet covered in wounds, staggering. Chaos; women in soldiers’s clothes; the desperate mothers of those who are too exhausted to go on. A starving soldier who ate too much bread and dropped dead. A soldier selling anything and everything for bread: his gun, clothes, shoes and boots, coats, horses’ feedbags, saddlebags, horses. Russian soldier Vasily Mishnin writes to his pregnant wife: We go to the depot to get our rifles. Good Lord, what’s all this? They’re covered in blood, black clotted lumps of it are hanging off them. . . . It is frightening even to sit or lie down here — the rifle is shaking in my hands. My hand comes down on something black: it turns out there are corpses here that haven’t been cleared away. My hair stands on end. I have to sit down. There is no point in staring into the distance — it is pitch dark. All I can feel is fear. I am so frightened of the shells that I want the ground to open up and swallow me. . . . Suddenly a screeching noise pierces the air, I feel a pang in my heart, something whistles past and explodes nearby. My dear Lord, I am so frightened — and I hear this buzzing in my ears. I leave my post and climb into my dugout. It is packed, everyone is shaking and asking again and again, “What’s going on? What’s going on?” One explosion follows another, and another. Two lads are running, shouting our for nurses. They are covered in blood. It is running down their cheeks and hands, and something else is dripping from underneath their bandages. They’re soon dead, shot to pieces. There is screaming, yelling, the earth is shaking from artillery fire and our dugout is rocking from side to side like a boat. . . . Our eyes are full of tears, we wipe them away, but they just keep coming because the shells are full of gas. We are terrified. . . . We will probably never see each other again — all it takes is an instant and I will be no more — and perhaps no one will be able to gather the scattered pieces of my body for burial. . . . A zeppelin attacked Ostrow in the night and dropped a few bombs, many killed. One woman and her two kids got blown to pieces that blew away in the wind. Australian corporal George Mitchell writes in his diary: And again I heard the sickening thud of a bullet. I looked at him in horror. The bullet had fearfully mashed his face and gone down his throat, rendering him dumb. But his eyes were dreadful to behold. How he squirmed in agony. There was nothing I could do for him, but pray that he might die swiftly. It took him about twenty minutes to accomplish this and by that time he had tangled his legs in pain and stiffened. I saw the waxy colour creep over his cheek and breathed freer. Turkish second lieutenant Mehmed Fasih writes in his diary: Though I keep picking off lice, there are plenty more — I just can’t get rid of them and am itching all over. My body is covered with red and purple blotches. . . . When I finally reach our trenches I find a large pool of blood. It has coagulated and turned black. Bits of brain, bone and flesh are mixed in with it. German doctor Ludwig Deppe writes in his diary: Behind us we have left destroyed fields, ransacked magazines, and, for the immediate future, starvation. We were no longer the agents of culture; our track was marked by death, plundering and evacuated villages. French captain Paul Truffrau writes in his diary: We reach the trench, dug out by joining up the shellholes and it stinks of bogs and decaying corpses. Stagnant water. . . . The smell of corpses everywhere. Russian officer Dmitry Oskin writes in his diary: The battle became so vicious that our soldiers started using spades to split Austrians’ skulls. This hand-to-hand fighting went on for at least two hours. Only nightfall stopped the butchery. American officer John Clark writes to his sweetheart: I was only beginning to see what war really is. . . . Outside of the enemy fire, it was a terrific strain on our men, for we were firing night and day — on a couple of occasions, for ten hours without any intermission. We spent our spare time burying the infantry dead which were scattered all around us. It was gruesome work, for the bodies had been lying on the battlefield for two, three or more days. On the crest just before us were light “tanks” which had been shattered by German shellfire. They were the most gruesome of all, for the charred bodies of their crews were still in or scattered about them. The unnamed Austrian officer writes his last words in his diary: The wounded groan and cry for their mothers. You have to shut your ears to it. . . . It is enough to drive you insane. Dead, wounded, massive losses. This is the end. Unprecedented slaughter, a horrific bloodbath. There is blood everywhere and the dead and bits of bodies lie scattered about so that Second only to the horrors on the battlefield are those that one endures in captivity. Russian soldier Alexei Zyikov writes in his diary: Hunger does not give you a moment’s peace and you are always dreaming of bread: good Russian bread! There is consternation in my soul when I watch people hurling themselves after a piece of bread and a spoonful of soup. We have to work pretty hard too, to the shouts and beatings of the guards, the mocking of the German public. We work from dawn till dusk, sweat mingling with blood; we curse the blows of the rifle butts; I find myself thinking about ending it all, such are the torments of my life in captivity! . . . Then there are those of us who eat potato peel: they take it out of the pit, wash it and boil it, eat it and say how delicious it is. Some consider it the greatest happiness to snatch food from the tub where the Germans throw their leftovers. War and the State The truth of Randolph Bourne’s classic statement, “War is the health of the state,” can be seen throughout the excerpts from the diaries and letters in Intimate Voices. To get a war to work — to get men to kill other men that have never aggressed against them and that they don’t even know — the state must do two things: convince men to love the state and to hate the members of other states. The first is always cloaked in patriotism, and leads to an acceptance of interventionism. The second is always cloaked in nationalism, and leads to hatred toward foreigners within one’s country. German schoolgirl Piete Kuhr writes in her diary: At school they talk of nothing but the war now. The girls are pleased that Germany is entering the field against its old enemy France. We have to learn new songs about the glory of war. The enthusiasm in our town is growing by the hour. . . . People wander through the streets in groups, shouting “Down with Serbia! Long live Germany!” Crowds of people are milling around in the streets, laughing, wishing each other good luck and joining in singing the national anthem. . . . Dear God, just bring the war to an end! I don’t look on it as glorious any more, in spite of “school holidays” and victories. . . . At school everyone is so much in favour of the war. . . . They scream so that the headmaster sees what a patriotic school he has. . . . Everyone talks of shortages. Most people are buying in such massive stocks that their cellars are full to bursting. Grandma refuses to do this. She says she doesn’t want to deprive the Fatherland of anything. We’re not hoarders. The Fatherland won’t let us starve. . . . To them [uncle and mother] “the German nation” is still everything. Fall with a cheer for the Fatherland, and you will die as a hero in their eyes. German officer Ernst Nopper writes in his diary: At the border post we strike up “Deutschland, Deutschland Über Alles.” French schoolboy Yves Congar writes in his diary: I can only think about war. I would like to be a soldier and fight. . . . Very well, if they want to starve us then they’ll see when, in the next war, the next generation goes to Germany and starves them. They are turning the French people against them and I’m happy about it. I have never hated them so much. . . . The Germans, fiends, thieves, murderers and arsonists that they are, set fire to everything. . . . The Boches’ behaviour in France is scandalous. The loot they are taking back to Germany is unbelievable: they’ll have enough to refurbish every one of their towns! But one day soon it will be our turn: we will go there and we will steal, burn and ransack! They had better watch out! Over in Germany they are almost as unhappy as we are. There is famine in all the big cities: Berlin, Dresden and Bavaria; I hope they all die! Russian soldier Alexei Zyikov writes in his diary: They boast to us that their governments send them bread and parcels from home. But we, Russians, get nothing: our punishment for fighting badly. Or, perhaps, Mother Russia has forgotten about us. Klara, the mother of Rudolf Hess, writes to her son: Of course I know that an armistice would mean your safe return, my sons, but your future and that of the Fatherland would be built on shaky foundations. . . . It would be cowardly of us to worry about you. Instead we should be proud that through our sons we are fighting for the salvation of the Fatherland. Polish widow Helena Jablonska writes in her diary: The Jews are frightened. The Russians are taking them in hand now and giving them a taste of the whip. They are being forced to clean the streets and remove manure. . . . The Jewish pogrom has been under way since yesterday evening. The Cossacks waited until the Jews set off to the synagogue for their prayers before setting upon them with whips. They were deaf to any pleas for mercy, regardless of age. . . . It pains me to hear the Germans bad-mouth Galicia. Today I overheard two lieutenants asking “Why on earth should the sons of Germany spill blood to defend this swinish country?” We, the Poles, are hated by everyone in this Austrian hotchpotch and are condemned to serve as prey for all of them. African Kande Kamara writes in his diary: We black African soldiers were very sorrowful about the white man’s war. There was never any soldier in the camp who knew why we were fighting. There was no time to think about it. I didn’t really care who was right — whether it was the French or the Germans — I went to fight with the French army and that was all I knew. The reason for war was never disclosed to any soldier. They didn’t tell us how they got into the war. We just fought and fought until we got exhausted and died. Day and night, we fought, killed ourselves, the enemies and everybody else. Australian corporal George Mitchell writes in his diary: A wounded Turk told us they regard Australians as fiends incarnate. British private Robert Cude writes in his diary: I long to be with battalion so that I can do my best to bereave a German family. I hate these swines. . . . It is a wonderful sight and one that I shall not forget. War such as this, on such a beautiful day seems to me to be quite correct and proper! . . . Men are racing to certain death, and jesting and smiling and cursing, yet wonderfully quiet in a sense, for one feels that one must kill, and as often as one can. The unnamed Austrian officer writes in his diary: Since yesterday my mind has been troubled by the thought of the many Austrian heroes who have given their lives defending the honour of Austria and the Habsburgs, while I entertained my thoughts of treason, all for the love of an unworthy [Italian] woman. I am disgusted at myself. Habsburg, I live for you and I shall die for you, too! . . . He who gives his life for the Fatherland and the honour of the Habsburgs shall be honoured and remembered for eternity. Russian officer Dmitry Oskin writes in his diary of his support for the ultimate form of state interventionism. First he records part of a speech he heard given by Lenin in support of Communism: “The main point is that land should be taken immediately from the landowners and given to the peasants without compensation. All ownership of land is to be eliminated.” Then he recounts his own comments: “We the soldier-peasants demand that the land be immediately decreed common property. That it is immediately taken from the landowners and given to local land committees.” Religion in War If there is ever a time when men get religious it is certainly in the midst of a war. The phenomenon of “fox hole religion” is understandable. What is interesting, however, is the religious ideas of some combatants when they go into the war. Men on both sides think that God is on their side. Turkish second lieutenant Mehmed Fasih writes in his diary: From the rear comes “Allah! Allah!” — the rallying cry of our soldiers. . . . One of his comrades tells us how Nuri said to him when they arrived at the Front together: “I implore God to let me become a martyr!” Oh Nuri! Your prayer was answered. We bury Nuri. It was God’s will that I would say the opening verse of the Koran over him. The African Kande Kamara writes in his diary: Coming from the background I came from, which was Muslim oriented, the only thing you thought about was Allah, death and life. . . . Whatever we thought was dedicated to the God Almighty alone. This attitude is not restricted to Muslims. The unnamed Austrian officer writes in his diary: Dear Lord, come to our aid, for we fight in the name of Justice, the Empire and the Faith. Dear Lord, steer the flight of the double eagle so that these beauteous lands, which had one time belonged to Austria, once again fall under the shadow of its mighty wings. . . . Cases of cholera. This is all we need. Is God no longer on our side? . . . Italy will pay for this, for the Lord sits in judgement up on high and he is wrathful. German schoolgirl Piete Kuhr writes in her diary: But we have faith in France and God, and comfort ourselves with the thought that over in Germany they are almost as unhappy as we are. Klara, the mother of Rudolf Hess writes to her son: Thank God the German Michael [the patron saint of Germany] has finally had the guts to stand firm until our rights to water and land have been secured. Women in Wartime One of the great tragedies of war is its demoralizing effect on women, either through subjugation or whoredom. Austrian doctor Josef Tomann writes in his diary: And then there are the fat-bellied gents from the commissariat, who stink of fat and go arm in arm with Przemysl’s finest ladies, most of who (and this is no exaggeration) have turned into prostitutes of the lowest order. The hospitals have been recruiting teenage girls as nurses, in some places there are up to 50 of them! . . . They are, with very few exceptions, utterly useless. Their main job is to satisfy the lust of the gentlemen officers and, rather shamefully, of a number of doctors, too. . . . New officers are coming in almost daily with cases of syphilis, gonorrhoea, and soft chancre. Some have all three at once! The poor girls and women feel so flattered when they get chatted up by one of these pestilent pigs in their spotless uniforms, with their shiny boots and buttons. . . . . Anything that can’t be carted off or used to pay one of the prostitutes for her services is burnt, so that the Germans don’t get it when they march in. British officer Richard Meinertzhagen writes in his diary: All the blacks are mad on looting, whether it is the Askaris or the porters, man, woman or child. It is also difficult to stop the blacks from raping women, because they see them as property, like cows or huts. African Kande Kamara writes in his diary: The only way to get to town was by sneaking out of camp. There were some white women who had mattresses and beds and invited you to their bedrooms. In fact they tried to keep you there. They gave you clothes, money, and everything. When the inspector came, he never saw you, because you were hiding under the bed or under the bed covers of that beautiful lady. That’s how some soldiers got left behind. None of them went back to Africa. Canadian Winnie McClare writes in a letter to his father: An awfull lot of fellow that go to London come back in bad shape and are sent to the V.D. hospitals. There is one V.D. hospital near here that has six hundred men in it. It is a shame that the fellows can’t keep away from it. Disillusion and Regret Occasionally, we read in Intimate Voices of the disillusion and regret of soldiers and civilians. The folly of war is sometimes recognized. German officer Ernst Nopper writes in his diary: And all this time the weather is so beautiful that the shooting seems absurd. Russian soldier Vasily Mishnin writes to his pregnant wife: What are we suffering for, what do I achieve by killing someone, even a German? . . . It is quite a peaceful scene when it’s quiet and no one is firing. This is our enemy? They look like good, normal people, they all want to live and yet here we are, gathered together to take each other’s lives away. British officer Richard Meinertzhagen writes in his diary: It seemed so odd that I should be having a meal today with people whom I was trying to kill yesterday. It seemed so wrong and made me wonder whether this really was war or whether we had all made a ghastly mistake. German officer Ernst Nopper writes in his diary: I no longer share most people’s enthusiasm for war. I think about the dying soldiers, not just Germans, but also French, English, Russian, Italian, Serbian and I don’t know who else. German schoolgirl Piete Kuhr writes in her diary: I don’t want any more soldiers to die. Millions are dead — and for what? For whose benefit? We must just make sure that there is never another war in the future. We must never again fall for the nonsense peddled by the older generation. And finally, the regret of Russian soldier Alexei Zyikov, who writes in his diary during Easter of 1916: Why did I lead such a debauched life? Why did I not cherish my family and friends? I don’t know. I loved adventure and now I am paying for it. I feel very sad. Must I really die like this, fruitlessly, with nothing worth repenting of? The argument that modern warfare has changed so much that these descriptions of World War I never happen — modern war really isn’t all that bad (unless of course you get killed) — is never made by the soldier who suffers psychological damage or psychiatric disorders the rest of his life, the forgotten civilians injured or disfigured in the conflict, or by those maimed or blown up by land mines years later. Such are the horrors of war.

The Christmas Truce December 25, 2004

Most American families have some traditions they observe every Christmas, even Jewish families. It might be decorating a tree, singing Christmas carols, shopping for bargains on Christmas Eve, attending church services, reading the biblical account of the birth of Christ, taking the kids to see the grandparents, driving around and looking at Christmas lights, eating at a particular restaurant, or watching It’s a Wonderful Life, Miracle on 34th Street, or A Christmas Carol.

What makes the World War I Christmas truce even more relevant this Christmas is that we are once again at war on Christmas and it is the 90th anniversary of the famous truce. The Christmas of 1914 was the first Christmas of the “war to end all wars.” The war would drag on through three more. The German, French, Belgium, and British troops engaged in killing each other did not just all of a sudden lay down their arms because it was Christmas. According to Weintraub, neither side had been “firing at mealtimes” and “friendly banter echoed across the lines.” The soldiers in their trenches were sometimes so close to each other that “they would throw newspapers, weighted with a stone, across to each other, and sometimes a ration tin.” In early December, a British general issued an order that forbade fraternization because “it discourages initiative in commanders, and destroys the offensive spirit in all ranks.” Yet, less than a week before Christmas, a British lieutenant wrote to his mother: Some Germans came out and held up their hands and began to take in some of their wounded and so we ourselves immediately got out of our trenches and began bringing in our wounded also. The Germans then beckoned to us and a lot of us went over and talked to them and they helped us to bury our dead. This lasted the whole morning and I talked to several of them and I must say they seemed extraordinarily fine men. . . . It seemed too ironical for words. There, the night before we had been having a terrific battle and the morning after, there we were smoking their cigarettes and they smoking ours.

No one knows for certain where and how the truce officially began. What is known is that men from both sides up and down the front agreed on informal truces for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. A Bavarian captain recalled that he shouted to his enemies that: “we didn’t wish to shoot and that we [should] make a Christmas truce. I said I would come from my side and we could speak with each other. First there was silence, then I shouted once more, invited them, and the British shouted u2018No shooting!’ Then a man came out of the[ir] trenches and I on my side did the same and so we came together and we shook hands — a bit cautiously!” An English captain wrote to his wife: I was in my dugout reading a paper and the mail was being dished out. It was reported that the Germans had lighted their trenches up all along the front. We had been calling to one another for some time Xmas wishes and other things. I went out and they shouted “no shooting” and then somehow the scene became a peaceful one. All our men got out of the trenches and sat on the parapet, the Germans did the same, and they talked to one another in English and broken English. I got on top of the trench and talked German and asked them to sing a German Volkslied, which they did, then our men sang quite well and each side clapped and cheered the other. A Scottish corporal relates his experiences: We shook hands, wished each other a Merry Xmas, and were soon conversing as if we had known each other for years. We were in front of their wire entanglements and surrounded by Germans — Fritz and I in the center talking, and Fritz occasionally translating to his friends what I was saying. We stood inside the circle like street-corner orators. Soon most of our company . . . hearing that I and some others had gone out, followed us; they called me “Fergie” in the Regiment, and to find out where I was in the darkness they kept calling out “Fergie.” The Germans, thinking it was an English greeting, answered “Fergie.” What a sight — little groups of Germans and British extending almost the length of our front! Out of the darkness we could hear laughter and see lighted matches. . . . Where they couldn’t talk the language they were making themselves understood by signs, and everyone seemed to be getting on nicely. Here we were laughing and chatting to men whom only a few hours before we were trying to kill! That last sentence alone shows the utter folly of war. It also shows that left to themselves, men would not naturally engage in such a senseless war like World War I. It takes the state to get men to hate and kill other men that have never aggressed against them and that they don’t even know. After a silent night and a day, the war continued — the commanders saw to it. A British general who visited the front was aghast that “sufficient attention” was not being paid to fighting the Germans. In a memorandum to his commanders he stated: I would add that, on my return, I was shown a report from one section of how, on Christmas Day, a friendly gathering had taken place of Germans and British on the neutral ground between the two lines, recounting that many officers had taken part in it. This is not only illustrative of the apathetic state we are gradually sinking into, apart also from illustrating that any orders I issue on the subject are useless, for I have issued the strictest orders that on no account is intercourse to be allowed between the opposing troops. To finish this war quickly, we must keep up the fighting spirit and do all we can to discourage friendly intercourse. I am calling for particulars as to names of officers and units who took part in this Christmas gathering, with a view to disciplinary action. Weintraub closes the book with a chapter entitled “What If — ?” But amid all that the author proposes that might or might not have been, one statement stands out: “The butchery in which hundreds of thousands of bodies were ground into the mud of the Western Front, leaving not an identifiable bone, would not have happened. The more than six thousand deaths every day over forty-six further months of war would not have occurred.” And now, ninety years later, we are again engaged in a war. The casualties may be less, but the state’s lies about the war have increased. The president maintains that the United States and the world are safer now than before the September 11th attacks. But does the rest of the world real feel safer? The situation described by Lew Rockwell just after Christmas two years ago has not changed: “The US remains the only government in human history to have dropped nuclear weapons on people, it has far more weapons than anyone else, and remains the only country that reserves to itself the right of first strike.” Instead of invading the world, the United States should declare a truce with the world. No more threats. No more bombs. No more troops or bases on foreign soil. No more spies. No more trade sanctions. No more embargoes. No more foreign aid bribes. No more foreign entanglements. No more simultaneously playing the world’s bully and policeman. In a word: non-interventionism; that is, the principles of our Founding Fathers. What is wrong with “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations”? What is wrong with avoiding “entangling alliances”? What is wrong with “having as little political connection as possible” with foreign nations? What is wrong with not going abroad “seeking monsters to destroy”? Can anyone honestly say that Bush’s principles are better than Jefferson’s principles?

They Knew Not Where They Were Going or

Why

May 28, 2005

In times of war, people do strange and irrational things. They also do things that they would never think of doing in peacetime — like killing and maiming people that never lifted a finger against them, that they didn’t know, and that they had never even spoken to. It was one hundred years ago that the first war ended in what was to be a very bloody century of war. The Russo-Japanese War began on the night of February 8, 1904, with the Battle of Port Arthur, a port on the Liaotung peninsula in Manchuria that served as the primary base for the Russian fleet in the Pacific. Port Arthur, which took its name from British Royal Navy Lieutenant William C. Arthur, was a strategic seaport coveted by Russian and Japan. Although the immediate cause of the war was the Japanese naval attack on Port Arthur, the Russo-Japanese War was preceded, as are most wars, by interventionism. Russia and Japan, at the expense of China, wanted control or “influence” in the Far East. After warring against China in the mid 1890s, Japan demanded control of Port Arthur. The European Powers objected, not because they respected Chinese sovereignty, but because they had their own ambitions in the Far East. Within a couple of years, Russia took control of Port Arthur, gaining a valuable ice-free port to supplement Vladivostok. Suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 resulted in more intervention by Japan and the European powers. Russian troops remained in Manchuria after the fighting ended. It was Russian refusal to make good on its promised withdrawal of Russian troops that led to the Russo-Japanese War. The outcome of the Battle of Port Arthur was inconclusive, but Japan was victorious when the Siege of Port Arthur ended on January 2, 1905. The Japanese also defeated the Russians at four major land battles and two major sea battles before the war effectively ended on May 28, 1905, with the defeat of the Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima. Nearly the entire Russian fleet, which had sailed all the way from the Baltic coast, was destroyed in this battle in the waters of Tsushima Straits (between the Japanese island of Kyushu and South Korea), along with over 4,300 men. The Japanese lost only three torpedo boats and a little over 100 men.

In 1904 Nicholas had been drawn into a disastrous war with Japan. He dispatched his troops with his blessing. Not that they knew where they were going or why. The Russian people believed the propaganda which promised a short, sharp, victorious war. But the Japanese people believed their propaganda which promised the same and proved to be right. It took the Russian navy’s Baltic Fleet six months on the high seas to make the engagement; only to be sunk in a single day at the Battle of Tsushima.

The Twenty-Year War in Iraq

January 17, 2011

“Why should a single American die for the Emir of Kuwait?” ~ Pat Buchanan The current war in Iraq – now near the end of its seventh year – did not really begin on March 20, 2003, when George W. Bush ordered the United States military to invade Iraq. It actually began twenty years ago on January 17, 1991, when another Bush, George H.W., ordered the United States military to invade Iraq the first time. After getting a green light from the U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, who told Saddam Hussein: “We have no opinion on your Arab-Arab conflicts, such as your dispute with Kuwait. Secretary Baker has directed me to emphasize the instruction, first given to Iraq in the 1960s, that the Kuwait issue is not associated with America,” Hussein invaded Kuwait, on August 2, 1990. But even after John Kelly, the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, testified to Congress that the “United States has no commitment to defend Kuwait and the US has no intention of defending Kuwait if it is attacked by Iraq,” Bush the elder sent 500,000 U.S. troops to that caldron known as the Middle East. After imposing sanctions on Iraq in August, the United Nations in November set a date of midnight on January 16 as the deadline for Iraq to withdraw its troops from Kuwait. Congress – ignoring the Constitution and refusing to issue a declaration of war – issued a resolution authorizing the president to use military force against Iraq, “Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 678.” The vote was 52-47 in the Senate and 250-183 in the House. Only two Republicans in the Senate and three in the House voted against the resolution. When Iraq failed to withdraw its troops from Kuwait by the deadline, the United States commenced bombing as Operation Desert Shield turned into Operation Desert Storm. The 88,500 tons of bombs dropped widely destroyed both military and civilian infrastructure. The U.S. ground assault, Operation Desert Sabre, begin on February 24. A cease-fire was declared four days later. For the United States, there were 148 battle deaths and 145 non-battle deaths. This means that 293 Americans did die for the emir of Kuwait. Among the dead U.S. soldiers were 15 women and 35 killed by “friendly fire.” The first American casualty of the war, LCDR Scott Speicher, was actually the last of the U.S. military dead to be identified, and just a couple of years ago. Tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers were also killed, plus several thousand Iraqi and Kuwaiti civilians. The current war in Iraq is but a delayed campaign in the war against Iraq. During the intermission there were tensions, threats, missile strikes, enforcement of no-fly zones, bombing raids, brutal sanctions that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children, infamously said to be “worth it” by U.S. ambassador to the UN (and later Secretary of State) Madeleine Albright, and a continued presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, which inflamed the Muslim world, created terrorists, and led to the attacks of 9/11. So, what should the United States have done when one autocratic Muslim state (Iraq) invaded another autocratic Muslim state (Kuwait)? The answer is the same no matter what country invades, bombs, attacks, or threatens another country – absolutely nothing. It is not the purpose of the U.S. government to be the policeman, security guard, mediator, and babysitter of the world. The preamble to the Constitution mentions providing for the common defense, promoting the general welfare, and securing the blessings of liberty “to ourselves and our Posterity,” not to the tired, poor, huddled masses, and wretched refuse on distant shores. The United States should be a beacon of liberty, leading the world by example, and not intervening or meddling in the affairs of other countries – for any reason. Not isolationism, of course, but in the words of Thomas Jefferson: “Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none,” yet doing “what is right, leaving the people of Europe to act their follies and crimes among themselves, while we pursue in good faith the paths of peace and prosperity.” And as I have maintained over and over again, the U.S. military should be engaged exclusively in defending the United States, not defending other countries, and certainly not attacking, invading, or occupying them. The U.S. military should be limited to defending the United States, securing U.S. borders, guarding U.S. shores, patrolling U.S. coasts, and enforcing no-fly zones over U.S. skies instead of defending, securing, guarding, patrolling, and enforcing in other countries. To do otherwise is to pervert the purpose of the military. The world is full of evil, and conflicts between peoples have existed since the beginning of time. The United States has neither the responsibility nor the resources to resolve every conflict and stamp out all the evil in the world. Any American concerned about oppression, human rights violations, sectarian violence, ill treatment of women, forced labor, child labor, persecution, genocide, famine, natural disasters, or injustice anywhere in the world is perfectly free to contribute his own money to or go and fight on behalf of some particular cause. Just don’t expect U.S. taxpayers to foot the bill for and U.S. soldiers to die for your cause. Freeing Kuwait from Iraq – even if “only” 293 Americans died, even if Saddam Hussein had been deposed, even if it hadn’t resulted in brutal sanctions, even if it hadn’t led to another war, and even if it had ensured the free flow of oil at market prices – was not worth one cent from the U.S. treasury or one drop of blood from an American soldier.

About Laurence M. Vance:

Laurence M. Vance is an author, a publisher, a lecturer, a freelance writer, the editor of the Classic Reprints series, and the director of the Francis Wayland Institute. He holds degrees in history, theology, accounting, and economics. The author of twenty-seven books, he has contributed over 900 articles and book reviews to both secular and religious periodicals. Vance's writings have appeared in a diverse group of publications including the Ancient Baptist Journal, Bible Editions & Versions, Campaign for Liberty, LewRockwell.com, the Independent Review, the Free Market, Liberty, Chronicles, the Journal of Libertarian Studies, the Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society, the Review of Biblical Literature, Freedom Daily, and the New American. His writing interests include economics, taxation, politics, government spending and corruption, theology, English Bible history, Greek grammar, and the folly of war. He is a regular columnist, blogger, and book reviewer for LewRockwell.com, and also writes a column for the Future of Freedom Foundation. Vance is a member of the Society of Biblical Literature, the Grace Evangelical Society, and the International Society of Bible Collectors, and is a policy adviser of the Future of Freedom Foundation and an associated scholar of the Ludwig von Mises Institute. See here for some articles by Laurence M. Vance that provide an overview of his worldview and philosophy. Independent Baptist Churches can contact Laurence M. Vance about hosting a King James Bible Conference. Laurence M. Vance: "Champion of liberty and peace"--Lew Rockwell, chairman of the Ludwig von Mises Institute Laurence M. Vance: "The gold standard in understanding war and peace"—Andrew Napolitano, Fox News Senior Judicial Analyst

Buy Laurence M. Vance Books

Here: War, Empire, and the Military: Essays on the Follies of War and U.S. Foreign Policy http://www.vancepublications.com/wem.htm

War, Christianity, and the State: Essays on the Follies of Christian Militarism http://www.vancepublications.com/wcs.htm

Christianity and War and Other Essays Against the Warfare State (2nd. ed.) http://www.vancepublications.com/cw2.htm

Laurence M. Vance Books: http://vancepublications.com/books%20by%20lmv.htm

Laurence M. Vance Website:

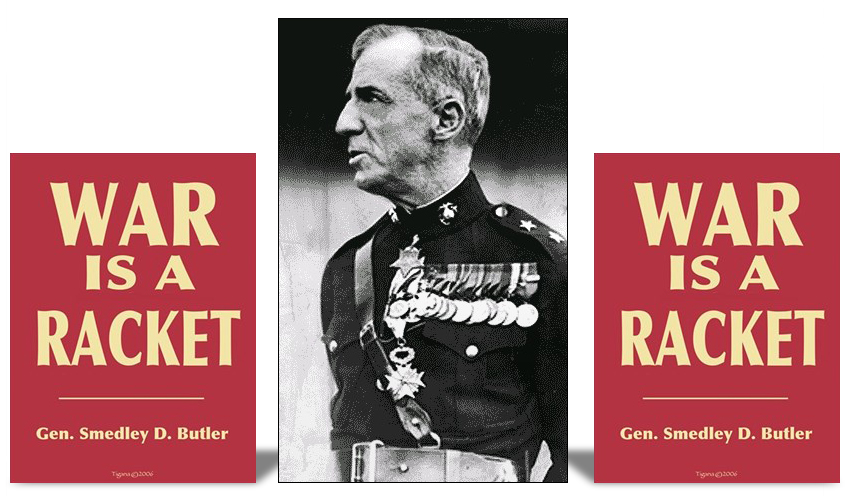

Things the Marine Corps Forgot to

Mention (Excerpt) U.S. Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler (1881—1940) — a Congressional Medal of Honor winner who could never be accused of being a pacifist and the author of : War is just a racket. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of people. Only a small inside group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few at the expense of the masses. I believe in adequate defense at the coastline and nothing else. If a nation comes over here to fight, then we’ll fight. The trouble with America is that when the dollar only earns 6 percent over here, then it gets restless and goes overseas to get 100 percent. Then the flag follows the dollar and the soldiers follow the flag. I wouldn’t go to war again as I have done to protect some lousy investment of the bankers. There are only two things we should fight for. One is the defense of our homes and the other is the Bill of Rights. War for any other reason is simply a racket. It may seem odd for me, a military man, to adopt such a comparison. Truthfulness compels me to. I spent 33 years and 4 months in active service as a member of our country’s most agile military force — the Marine Corps. I served in all commissioned ranks from second lieutenant to Major General. And during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism. Butler also recognized the mental effect of military service: Like all members of the military profession I never had an original thought until I left the service. My mental faculties remained in suspended animation while I obeyed the orders of higher-ups.

The Corbett Report First published at 13:16 UTC on January 22nd, 2020 SHOW NOTES AND MP3: https://www.corbettreport.com/?p=34783 Have you heard of Major General Smedley Butler? If not, you might want to ask yourself why that is. As one of the most highly decorated Marines in the history of the US Marine Corps and as a passionate and eloquent speaker about the racket that is war, Smedley Butler deserves to be a household name. Find out more in today's edition of Questions For Corbett.

Waging Peace in Vietnam: Columbia SIPA | Oct 25, 2019 The Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies presents the panel "Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans who Opposed the War" on Friday, October 18, 2019. Learn more: https://events.columbia.edu/cal/event...

SIR! NO SIR!

In the 1960’s an anti-war movement emerged that altered the course of history. This movement didn’t take place on college campuses, but in barracks and on aircraft carriers. It flourished in army stockades, navy brigs and in the dingy towns that surround military bases. It penetrated elite military colleges like West Point. And it spread throughout the battlefields of Vietnam. It was a movement no one expected, least of all those in it. Hundreds went to prison and thousands into exile. And by 1971 it had, in the words of one colonel, infested the entire armed services. Yet today few people know about the GI movement against the war in Vietnam. http://www.sirnosir.com/the_film/synopsis.html

LINKS: [ AL-QAEDA EXPOSED!! ] , SYRIA , YEMEN , RAND Corporation , Troops Protect Government Drug Dealing

No war on Iran: The Grayzone | Jan 7, 2020 Red Lines host Anya Parampil speaks with Ben Becker, an organizer with the ANSWER coalition, to discuss the growing anti-war movement in the US. Over the weekend, thousands of US citizens took to the streets in up to 90 cities in order to voice their opposition to the Trump Administration's push to war with Iran. Ben and Anya talk about the struggles faced by the anti-war movement over the years what makes organizing massive resistance to war policy possible.

-----------------------------------------

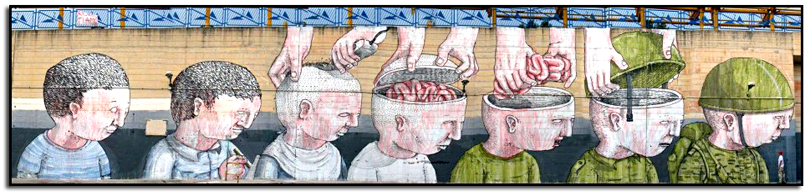

...Or, They Can Continue To Be Pawns.

"Military men are just dumb, stupid animals to be used as pawns in foreign policy." - Henry Kissinger -

“If soldiers were to begin to think, not one of them would

remain in the army.”

Christian,

| ||||||||||||

| << Previous 1... 5 6 [7] 8 9 Next >> |

Brief and localized pre-holiday truces were springing up, usually initiated by the Germans. As

Christmas Day approached, some German troops put up small Christmas trees on the parapets of their trenches.

On Christmas Eve they began to sing Stille Nacht (“Silent Night”). Placards with Christmas greetings were set

up by both sides. On Christmas Day, both sides buried their dead who had been lying in “No Man’s Land.” They

chatted, exchanged souvenirs, shook hands, ate and drank together, played football, had joint religious

services, and smoked each other’s tobacco. They also took pictures.

Brief and localized pre-holiday truces were springing up, usually initiated by the Germans. As

Christmas Day approached, some German troops put up small Christmas trees on the parapets of their trenches.

On Christmas Eve they began to sing Stille Nacht (“Silent Night”). Placards with Christmas greetings were set

up by both sides. On Christmas Day, both sides buried their dead who had been lying in “No Man’s Land.” They

chatted, exchanged souvenirs, shook hands, ate and drank together, played football, had joint religious

services, and smoked each other’s tobacco. They also took pictures.